I recently discovered on a visit to the Canadian Maritime provinces that a large number of the population are descended from Irish immigrants. In the years between 1770 and 1780 more than 100 ships and thousands of people left Irish ports for the fishery industry in Newfoundland and Labrador, and Nova Scotia. These migrations were some of the most substantial movements of Irish people across the Atlantic in the 18th century. The most “Irish” city is St John’s in Newfoundland, but Irish culture is found in all of the Maritimes. And we have a local connection with Halifax in Nova Scotia - RMS Titanic.

Halifax, provincial capital of Nova Scotia, was founded in 1749 by the British Navy which took advantage of its large very deep natural harbour, which does not freeze over, for a naval base. Before the atomic bomb the largest man-made explosion took place here in 1917 when a French ship loaded with explosive picric acid, TNT, and high octane fuel collided with a Belgian ship. The resulting explosion killed 2,000 people and destroyed two square miles of Halifax. The memorial is three tall red and white columns. The city has a very fine Maritime Museum featuring a permanent Titanic exhibition together with lots of other ships' models, fog bells, anchors etc., including a scale model of the Empress of Britain that my brother sailed on to Canada, and one of the Castle line that my husband went on to South Africa as a child.

One of the most popular city tours is a very poignant visit to the Fairview Lawn Cemetery where visitors can see the headstones of the victims who were brought ashore after the Titanic disaster. The survivors in lifeboats, including three dogs, were rescued by RMS Carpathia and taken to New York, her intended destination, but it fell to the seamen of Halifax to retrieve bodies from the sea. The crew of the CS Mackay-Bennett were cablemen who were responsible for laying the French transatlantic cable and were experienced in dealing with heavy seas. Their boat, built with a deep hold for carrying many lengths of heavy cable, had enough storage space for 100 coffins, ice, and other equipment for the sad task of recovery. Some 116 victims were buried at sea, and 59 sent back to their American families by train, or returned to England. The Mackay-Bennett recovered 330 casualties.

When the bodies were brought to the temporary mortuary set up at the curling rink in the city, all pieces of clothing were listed and searched for some sort of identification or hidden money or jewellery. It was common practice in those days that valuables or currency might be sewn into false pockets or hems of garments, especially if you were sharing accommodation with strangers. And so a number of people were identified, sent back to their families or buried in cemeteries according to their supposed faith. There was consternation when it was discovered in later years that a Catholic had been buried by mistake in the Jewish area at Fairview. This was because the gentleman, who was French, was on the run from his estranged wife, together with his two sons, and was using an assumed name which sounded Jewish. He died but the two boys were saved and his wife went over to New York to be reunited with them. Male passengers were buried in blue suits and the women in white chemises.

In the dedicated space reserved for the Titanic burials, there are 121 black granite headstones supplied by the White Star Line, engraved with the body’s Retrieval Identification Number and a few names of those who had some sort of ID on them, or met a description supplied by friends or family. The headstones are laid out in the form of a ship’s bows pointing east as the shipwreck took place some 600 kilometres east of Halifax. They were numbered for identification purposes in the order they were taken from amongst the debris in the ocean, and this new method was later used in forensic investigation of incidents where large numbers of people were involved, and specifically to identify people killed in the 1917 Halifax explosion.

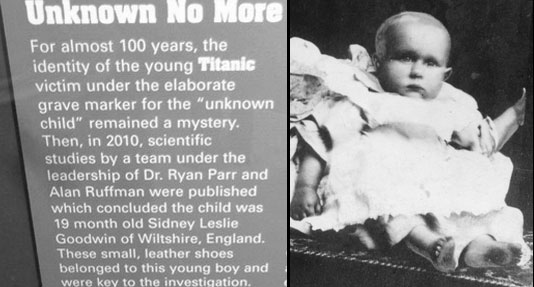

All Titanic deaths were accorded the date of 15th April as the ship broke apart and went beneath the waves just after 2am on the 15th. We saw the headstone of Jack Dawson, RI No.227, played by Leo. DiCaprio in the film. He was a real person but the character Rose was not! People leave flowers at his stone as they do also at the stone of the Unknown Child RI No.4, Description: Male Child, Fair Hair, Estimated Age 2, Clothing: Grey coat with fur on collar and cuffs, brown serge frock, petticoat, flannel garment, pink woollen singlet, stockings and brown shoes.

When everything had been investigated the clothing was gathered together and put on a bonfire to deter souvenir hunters. On the top of the pile was a pair of children’s little buttoned shoes. One of the policemen removed them, why we don’t know, but he kept them with a note saying “Shoes belonging to the Unknown Child, No 4” and they were found in his attic after he died. They are on exhibition in the Halifax Maritime Museum's Titanic Exhibition room, alone and highlighted in a special glass case. It is a very moving sight and reminded me of the piles of shoes taken from Belsen Concentration Camp and displayed in the Holocaust Museum in Israel. There, a number of the children’s shoes had their names written inside which helped with identification.

Male Child No 4 has an individual headstone, paid for by the crew of the Mackay Bennet as a representative of all the children who were lost or recovered and buried at sea. A copper pendant was placed in the coffin engraved with the words “Our Babe”. Vincent Astor had offered a huge reward to whoever found the body of his father, John Jacob Astor. The Mackay-Bennett crew did this and got $2,500 each.

Some years later, in 2010, with the development of DNA, combined with the donation of the little shoes by the policeman’s family to the museum, someone had the idea of trying again to identify the child. There appeared to be a faint impression of the maker’s name on the shoes. They were sent to the FBI laboratory in Quantico, Virginia, where strong imaging cameras showed the makers to be in Wiltshire. Assuming that, in those days, the shoes would have been made and bought locally, an appeal was made for anyone who had family including a small child known to have been lost on the Titanic. A response came from cousins of the Goodwins, who said that they had lost a family of parents, Frederick and Augusta Goodwin, and their six children, including a baby of 19 months. The family had been bound for a new life in Niagara Falls where they were to join other family members. Permission was granted by the Canadian government to disinter the little body of the Unknown Child and DNA tests were carried out using two of his baby teeth. The tests were successful in proving the family connection through the mother’s side of the family.

Now identified as Sidney Leslie Goodwin, born Sept 9, 1910, died April 15, 1912, his name and birth date were added to the headstone in Fairlawn Cemetery, no longer the Unknown Child. The other seven members of his family, his parents, and sisters and brothers, Lillian, Charles, William, Jessie and Harold had perished and were never found. At a memorial service for Sidney in 2008, the names of the other 50 children lost were read out and the church bell tolled for each one.