Bangor Historical Society welcomed guest speaker Alf McCreary to the opening meeting of the 2011-2012 season. His subject was the history of the port of Belfast on which he has recently written a book. He was welcomed by the chairman Bob McKinley who mentioned that the father and brother of one of our members, Jean Green, had been Harbour Commissioners.

Bangor Historical Society welcomed guest speaker Alf McCreary to the opening meeting of the 2011-2012 season. His subject was the history of the port of Belfast on which he has recently written a book. He was welcomed by the chairman Bob McKinley who mentioned that the father and brother of one of our members, Jean Green, had been Harbour Commissioners.

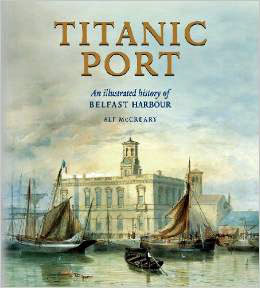

Mr McCreary explained that the idea for his book “Titanic Port” had come from the chairman of the Belfast Harbour Commissioners. He was taken to see the archives. He found these very interesting and mentioned a few of the items such as the photographs of the Duke and Duchess of York at Belfast Harbour and the opening of the harbour airport by Mrs. Neville Chamberlain shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War. He was intrigued by the history revealed by the archives and agreed to write the book. It took him eight to nine months to go through the archive. There was a treasure house of material dating back to the late eighteenth century.

He now faced the problem of how to arrange the material in order to make a good story. He said the first point was to tell a good story. The book was not about dates or ship building, but about people such as Harland, Pirrie and Wolff.

The back cover of the book has a picture dating from 1924. It shows the Harbour Commissioners all dressed up to meet the Duke and Duchess of York. They had run the harbour from the early nineteenth century and were responsible for reclaiming land which made the harbour what it is today. The choice of title was important as it had to be one which would get people’s attention in a bookshop. It was agreed to call it Titanic Port. The front cover has a striking painting of the Harbour Office in 1857. It also shows Sinclair Seaman’s Church in the distance. The other picture on the back cover shows the Titanic leaving Belfast.

Mr. McCreary decided to adopt a linear, rather than a thematic approach in the book. He looked at existing books on the subject, but they were not very good. In 1947 books were published for the centenary of the establishment of the Harbour Commissioners. In 1985 a book about the harbour was written by two engineers, but it was essentially an engineering history rather than a general one.

In 1613 the town of Belfast was incorporated by James I. It was a time of important developments elsewhere, with the establishment of colonies in North America and the translation of the Bible, now known as the Authorized Version. The charter allowed the official building of a landing stage and quay in Belfast. Belfast Lough was then known as Carrickfergus Lough and the main port in the area was Carrickfergus. Belfast harbour was landlocked and muddy and ships anchored in the Pool of Garmoyle while their cargoes was transferred into boats to reach the quay.

The Donegall family who were the landlords of Belfast would not give money for the development of the port. Eventually the Corporation applied to the Irish Parliament for assistance. They did not receive any money, but did get permission to dig out the harbour and raise money.

From the 1830s the first and second cuts were made to deepen and extend the harbour. The material excavated was used to create Dargan’s Island. On this area was created a park with a zoo, aviary, walks etc. Concerts were held, but drink and party tunes were banned. There was also a Crystal Palace which burned down. The island was later renamed Queen’s Island in honour of Queen Victoria who visited the town in 1849.

William Dargan, who was responsible for improvements to the port, was a remarkable man. He was also a railway contractor. Mr. McCreary went to Dublin to carry out further research on him. He was a great philanthropist and the National Gallery in Dublin has a Dargan Wing. Mr. McCreary felt that Mr. Dargan did not receive the credit he deserved and even his portrait was in store rather than hanging in the gallery. Mr. Dargan was also responsible for the viaduct at Newry.

Shipbuilding was an important industry in Belfast. William Ritchie, a Scot, produced wooden vessels. Then the Harbour Commissioners funded the first steel ship. Hickson was another shipbuilding pioneer, but his business failed and Harland took over. He was joined by the nephew of Gustav Wolff and thus the firm of Harland and Wolff was created. Edward Harland was the son of a Yorkshire doctor. He was a brilliant man, but was also said to be cold and hard. Mr. McCreary wondered if this was because his mother had died when he was 14. Harland married a girl from Markethill, but they had no children. Wolff was the financial expert. He was from Germany and was very different to Harland as he was a small man and a bit of a dandy. He remained a bachelor. It was said that Harland built the ships, Pirrie got the orders and Wolff smoked the company cigars.

Captain Pirrie owned ships in America. He got involved in the Franco-Spanish War and was captured by the French. He then made his way back to Belfast and became a Harbour Commissioner. His grandson was born in Canada, but when his father died he came home. He took over Harland & Wolff near the end of the nineteenth century and became one of the biggest men in British shipbuilding. He was given the title of Lord Pirrie.

Meanwhile Belfast and its harbour were booming, unhampered by the type of planning restrictions that exist today. In 1854 the first Harbour office was built. Belfast made a fortune from linen during the American Civil War when the cotton industry suffered major problems. By the end of the century Belfast was larger than Dublin and had been created a city. Within 20 years, however, things had gone down hill: the unrest over Home Rule, the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, the out break of the First World War and the subsequent loss of life at the Somme in 1916.

By the 1930s Belfast was affected by the Great Depression. The Harbour mirrored the economic difficulties as shipbuilding declined. One important development was the creation of the Harbour airport, using mud from the harbour.

Belfast played a vital role in the Second World War, especially after the fall of France in 1940. DeValera would not allow Britain to use Irish ports as the Irish Free State was neutral. Thus Belfast, Larne and Fermanagh played an important role in the Battle of the Atlantic. American troops arrived and were welcomed in places such as Bangor. In 1941 the harbour was a target for German bombers. Mr. McCreary met a lady whose husband had written about the raids. He had traced some of the pilots who had flown in the air raids over the city. She offered to let Mr. McCreary read her husband’s manuscript. One of the pilots had been an artist and sculptor. He was on a mission to bomb Dumbarton in Scotland, but the cloud base made this difficult. Instead they flew over Belfast on a cloudless night. He released two parachute bombs, one of which destroyed a flour mill. As they were flying home he could see the flames. The pilot bombed Belfast again, but was then switched to the Russian front. He flew 200 sorties and survived to return to his work as a sculptor. When he was traced by the Belfast man he said he was sorry about what happened.

In the 1950s the era of the big containers started. Harland and Wolff was still building magnificent ships like the Canberra, but was losing money. The Canberra was launched by Dame Patti Menzies, wife of the Australian Prime Minister.

The 1970s were a bad time for Belfast. One of the questions often raised is why the harbour was not bombed. The reason is that both sides realised it would not suit them as the dockers were both Protestant and Roman Catholic.

Now the harbour has expanded greatly and there is new infrastructure such as that near the Fortwilliam Roundabout. Events such as the Tall Ships race mean the people of Belfast are reclaiming the harbour. It does, however, remain a lifeline for Northern Ireland. Most imports come up the Lough day and night.

One aspect of the history of the harbour which formed an important part of the book was the story of the Titanic. It was finished and sank in the same year: 1912. Mr. McCreary pointed out that the story did not end there. People were ashamed of what happened and did not talk about it for 70 years. Even Harland & Wolff did not mention it: it was just another ship. Several events brought the story of the Titanic forward again: Robert Ballard’s discovery of the wreck about 1985 & his film and book about it; and James Cameron’s film. The story of the Titanic then began to take off with exhibitions etc. Harland and Wolff then began to admit to the ship and the whole thing has grown hugely.

Mr. McCreary warned that events in 2012 should commemorate the Titanic, not celebrate it as many lives were lost and it is a graveyard. It would be appropriate to celebrate the workmanship which created it. Mr. McCreary went to Halifax, Nova Scotia where he visited the graveyard where bodies which were recovered from the sea were buried. A ship filled with ice, coffins and sacks for the Third class passengers had been sent from the port to recover bodies. The Captain found the sad sight of bodies with lifejackets, their heads bobbing above the surface of the sea. Mr. McCreary mentioned Mike McKimm’s programmes for the BBC on the Titanic. One of the graves at Halifax was of a man named McQuillan. A lady identified him as her grandfather and said she did not know that there was a grave. The BBC flew her out to Halifax to visit it. He had changed places with another man who wanted to stay behind because his wife was expecting a baby. Mr. McCreary feels that the Titanic has been reclaimed for Belfast and people should take pride in the engineering etc.

Mr. McCreary felt a sense of loss when the book was finished. He praised the designers, the Harbour Commissioners and the team who produced it. He called it his Magnum Opus.

The book was launched in the Harbour Office and then next day in the House of Lords in London. Those present included Lord Trimble and the Secretary of State Owen Paterson. Later the book was launched in New York in the Metropolitan Club with a black tie affair. The building had been erected with money from J.P.Morgan, the financier, whose company owned the White Star Line and thus financed the Titanic. He had been blackballed by a club he wanted to join and so formed his own.

Members found this a fascinating talk and had the opportunity to ask questions. He explained how the Thompson Dock had been built in 1911 of a size to take the Titanic. He also explained about her sister ships the Olympic which was broken up after many years service and the Britannic which struck a mine off a Greek Island during the First World War. The three ships had been conceived as rivals to the Cunard ships with the stress on opulence and elegance, not speed.